by Cindy Dell Clark

Mythology is a living entity of culture in which cross-generational discourse can play a lively role. American Christmas and its Santa Claus mythology are a case in point. My early fieldwork on Santa Claus (conducted in the Midwest in the late 80s) showed that children’s perceptions of Santa and his reindeer carried impact on how family ritual was carried out. This is how I wrote about this issue in the book Flights of Fancy, Leaps  of Faith (University of Chicago Press, 1995) as specifically applied to Santa’s red-nosed reindeer, Rudolph.

of Faith (University of Chicago Press, 1995) as specifically applied to Santa’s red-nosed reindeer, Rudolph.

Children have mythologized Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer, who guides Santa’s sleigh with his bright red nose, an element of the Santa Claus myth often overlooked by adults. To leave out Rudolph seems mistaken to most children, who have embraced this misfit hero as so real that they often leave Rudolph an offering of a carrot or apple on Christmas Eve. (Rudolph conforms to a motif common in children’s folklore – the “ugly duckling” motif; in that motif, the very trait that makes someone a misfit is found to yield outstanding talent or specialness.) Rudolph was left out of the story in the movie  Ernest Saves Christmas, a fact about which juvenile moviegoers (in the audience I observed) complained aloud. When recalling how they once looked up in the sky and saw Santa’s sleigh, informants sometimes said they saw Rudolph, too.

Ernest Saves Christmas, a fact about which juvenile moviegoers (in the audience I observed) complained aloud. When recalling how they once looked up in the sky and saw Santa’s sleigh, informants sometimes said they saw Rudolph, too.

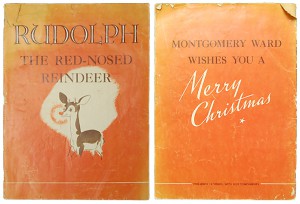

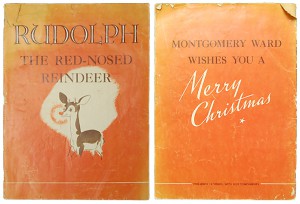

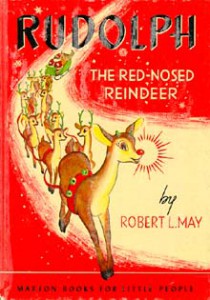

Children’s collective belief in Rudolph is all the more remarkable given how recently this cervid creature entered the Christmas lexicon, not via poetry or art (as Santa was shaped by Clement Clark Moore’s famous 1823 poem and Thomas Nast’s 1863 illustrations) but via commerce – Rudolph was a character in a flyer distributed by the mail order catalog Montgomery Ward.  Rudolph’s invention dates to 1939, buoyed on in 1949 in a popular song written by Johnny Marks. In less than two generations, Rudolph has a hold on the mythological imagination of the young, as a character with whom they identify. Children write notes and letters to Rudolph. The idea that Rudolph’s “special

Rudolph’s invention dates to 1939, buoyed on in 1949 in a popular song written by Johnny Marks. In less than two generations, Rudolph has a hold on the mythological imagination of the young, as a character with whom they identify. Children write notes and letters to Rudolph. The idea that Rudolph’s “special

power” derives from the red nose that made him a social anomaly

resonates with American children (“If there’s a big fog he can light up his nose and then show Santa the way”). These same kids are also fans of other mutants-turned-superheroes, exhibited by the sustained popularity of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Spiderman, and many more. Rudolph is a self-actualized hero because he is true to his individual specialness, a trait important to young folk in the world’s most individualist society. Santa is God-like, the source of much magic, to young believers. Less directly, Rudolph taps into enchantment by being true to his individual calling.

Immediately after Christmas in 2014, I conducted interviews with Jewish kids aged 6 to 8 years and their parents. I found that Rudolph was a compelling figure within the mythopoetics of Christmas, even among kids who celebrated Chanukah, not Christmas. Jewish children’s beliefs about Santa

varied. Some discounted Santa’s reality, others believed in Santa’s reality despite the fact that he doesn’t visit Jewish kids’ homes. A few who believed in Santa envied the kids he visited. Even among non-believers, though, Rudolph was a compelling figure.

Judy, an eight-year-old girl who lived in a neighborhood with many other Jewish families, had told her mother (the week before Christmas) “I wish we were Christian to celebrate.” Judy was familiar with Christmas, since her maternal grandparents (who were in a Christian-Jewish marriage) celebrated the Christian holiday, including presents on December 25. Judy, like other kids being raised in Jewish families, couldn’t help but be intimately familiar

Judy, an eight-year-old girl who lived in a neighborhood with many other Jewish families, had told her mother (the week before Christmas) “I wish we were Christian to celebrate.” Judy was familiar with Christmas, since her maternal grandparents (who were in a Christian-Jewish marriage) celebrated the Christian holiday, including presents on December 25. Judy, like other kids being raised in Jewish families, couldn’t help but be intimately familiar

with the entire iconography of Christmas, given its saturation in the majority culture. Jewish kids watch movies about the North Pole, Santa, his elves, and his reindeer for these are both hard to avoid at yuletide, as well as good entertainment even for non-believers.

By sheer exposure to Christmas movies and hype, Jewish kids left out of the Santa ritual still learned all the nuanced details of the Santa Claus mythology, but through a more marginalizing lens. Judy, for instance, was quite aware that Rudolph played the role of “Santa’s head reindeer.” In recounting stories (and a song) about Rudolph, she remembered best the way that others made fun of Rudolph, the fact that his exceptionality (red nose) led to being socially marginalized by peers. “Santa felt bad for him,” she recalled, suggesting that Santa’s sympathies lay with the outcast rather than the others who rejected and teased Rudolph.

Another mother I interviewed in 2014 drew a direct association between Rudolph and the actual lives of her children. When considering narratives about Rudolph, she revealed, her kids “notice how Rudolph might be sad, or be pushed aside … because he’s different.” This mother’s face showed a lingering sadness and her eyes filled with tears, as she explained that both of her two children had known the experience of being treated in a mean way by other children. Her son Randy, age eight, did not mention being ostracized when I talked with him. But he volunteered that he related to the

poetic trope of Rudolph as a  “misfit.” He prceived Rudolph as admirable, a figure who by virtue of exceptionality had attractive adventures. “Red noses are awesome,” Randy intoned, because “then you can see in the dark.”

“misfit.” He prceived Rudolph as admirable, a figure who by virtue of exceptionality had attractive adventures. “Red noses are awesome,” Randy intoned, because “then you can see in the dark.”

Without exception, the Jewish children I visited had been taught not to disturb the beliefs of others who regarded Santa and his reindeer as real. Along the divide between Jews and Christians, Christmas is a both a test of and opportunity for pluralism. From navigating the Christmas dilemma (as one mom called it) kids who are members of a minority religion learn how to live and let live. The magic of Rudolph, it would seem, lies ultimately in the capacity to remind us that exceptionality is valuable in the American cultural context, perhaps especially so to those who are in the minority.

of Faith (University of Chicago Press, 1995)

of Faith (University of Chicago Press, 1995)

Judy, an eight-year-old girl who lived in a neighborhood with many other Jewish families, had told her mother (the week before Christmas) “I wish we were Christian to celebrate.” Judy was familiar with Christmas, since her maternal grandparents (who were in a Christian-Jewish marriage) celebrated the Christian holiday, including presents on December 25. Judy, like other kids being raised in Jewish families, couldn’t help but be intimately familiar

Judy, an eight-year-old girl who lived in a neighborhood with many other Jewish families, had told her mother (the week before Christmas) “I wish we were Christian to celebrate.” Judy was familiar with Christmas, since her maternal grandparents (who were in a Christian-Jewish marriage) celebrated the Christian holiday, including presents on December 25. Judy, like other kids being raised in Jewish families, couldn’t help but be intimately familiar “misfit.” He prceived Rudolph as admirable, a figure who by virtue of exceptionality had attractive adventures. “Red noses are awesome,” Randy intoned, because “then you can see in the dark.”

“misfit.” He prceived Rudolph as admirable, a figure who by virtue of exceptionality had attractive adventures. “Red noses are awesome,” Randy intoned, because “then you can see in the dark.”