December 2023

Undocumented young people and the slippery slope of exclusion

Meloni, Francesca, 2023. Ways of Belonging: Undocumented Youth in the Shadow of Illegality. Rutgers University Press

“By being ‘illegal,’ you are a target, so you are easily hurt. You feel obliged to hide or to run because that is the way it is.” – Elizabeth

In Canada, as in many other countries around the world, undocumented young people are struggling to access social rights such as education and healthcare. Their lives are shaped by chronic uncertainty and invisibility due to restrictive anti-migration policies, leaving thousands of young people caught between the movements of hiding and running for fear of being deported. How do these young people navigate everyday interactions when they have to hide themselves and their legal status? How do they relate to their social environment when they might be deported and separated from their friends at any moment?

My book Ways of Belonging examines these questions, bringing into conversation the day-to-day experiences of such young people who live in Canada with their families, and the perspectives of the institutions who fail to recognize them. I focus on a specific form of exclusion for undocumented children: access to education. Undocumented young people are not named in national and provincial laws, which leads schools to arbitrarily decide what documents are required and consequently who is entitled to attend.

This book emerged from my experience of working as part of a larger study on access to health care for undocumented women and children, and of co-establishing a working group on access to education for undocumented young people. My involvement in the working group allowed me to have a more meaningful role for the communities I worked with. It also meant that I took a clearer ethical stand, and a messier research role, in relation to the injustices that undocumented families suffered.

As I became involved in action with other researchers and community organizations, I slowly assembled the different perspectives that compose denied access: the fear of families; the struggle of young people with daily invisibility; the confusion of school boards with the absence of guidelines; and the ignorance of the Ministry of Education that these young people even exist.

Drawing on these discordant perspectives, I show how the state makes people ‘illegal’ not only through explicit policies of exclusion such as deportation and surveillance, but also through what I term ‘structural invisibility’: norms and practices that are that are deliberately left ambiguous, silent, half-written, or whispered and that erase individuals at a social, legal, and political level.

Francesca Meloni is Assistant Professor of Social Justice at the School of Education, Communication & Society, King’s College London. Her research focuses on contemporary processes of migration and social exclusion. She is interested in the interface between migration, policy, race, and age, and in the impact of legal status on the experiences of belonging and access to welfare services. Her work has appeared in interdisciplinary journals such as Anthropological Theory, Social Science & Medicine, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Image credit: Arm Rest with a Purpose by Rabia Farooqui

November 2023

Imagination and Children Changing Cultures in Amazonia

Morelli, Camilla. 2023. Children of the Rainforest: Shaping the Future in Amazonia. Rutgers University Press: N.J.

When I started carrying out fieldwork with children in Amazonian Peru, over ten years ago, my original goal was to examine their relationship with the forest environment and its inhabitants. I had never been to Amazonia before, and in my own imagination I pictured the children playing in and talking about the forest all day long, assuming that it would be the foundation of their imaginative and practical lives.

But the children had little if any desire to talk about the forest. Whenever I asked them about animals, hunting, or spirits, they would shrug and say, “Go and ask my grandparents”. They rarely mentioned the forest spontaneously and barely ever accompanied the adults on hunting treks, although the elderly recalled doing so when they themselves were young.

The children were far more interested in the equipment I had brought with me, like my camera and laptop, and would much rather listen to stories about my homeland than answer my questions about theirs. From our very first interactions, they steered our conversations out of the forest world cherished by the older generations and into an imaginative terrain crisscrossed by concrete paving, lit by the glow of electric lights and television screens, and centered around the practices and possessions of urban people.

Having worked with them for over a decade, returning every year to their villages in the forest, I have watched these children grow into new kinds of persons compared with the generations before them. My book, “Children of the Rainforest” traces their journeys toward uncharted horizons, and in the process propose an ethnographic theory of social change and the future of Amazonia grounded in children’s own perspectives.

Camilla Morelli is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol, UK. Her current research projects, “Waves of Change” and “Animating the Future”, use animation co-production with young people living in rainforest and coastal communities with uncertain futures, to explore the adulthoods they desire and to amplify young voices that remain unheard.

October 2023

Are they just kidding? Taking children seriously as research participants

Fians, Guilherme. 2023. The Others’ Others: When Taking Our Natives Seriously is Not Enough. Critique of Anthropology 43 (2): 167-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X231175982.

In the late nineteenth century, as the early anthropologists sought ways to justify their novel venture of scientifically describing non-Western populations, what better way to situate the relevance of ‘primitive’ thought if not through a comparison with Western children? From James Frazer and Edward Tylor to Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, anthropologists approached the ‘primitives’ as the infancy of humankind, deploying Western children’s intellectual progress as a metaphor for human progress.

Over the twentieth century, the ‘primitive’ peoples formerly taken as tokens to reveal the stages of humankind’s sociocultural progress gradually came to be seen as legitimate subjects in themselves. Yet, as the parallels between the ‘primitives’ and Western children ceased to justify anthropology’s evolutionist endeavor, children lost prominence in mainstream anthropological theory. My article retraces these debates by asking: While anthropologists have learned to ‘take their natives seriously’, to what extent have they been taking seriously those ‘natives’ currently marginalized under the label/subfield Anthropology of Childhood?

The way developmental psychologists and early anthropologists approached ‘reality’ and ‘fantasy’ enticed me to explore how children – who, like the ‘primitives’, were deemed unable to distinguish between concrete existence and ritual/play – understood such distinctions.

As I observed during my ethnographic fieldwork with children between 2 and 7 years old in a school in Rio de Janeiro, most role-play begins with a negotiation on what to play, on the characters to be performed and their potentialities: who will be Anna and Elsa when playing Disney’s Frozen; whether one can play a superhero while playing family; and whether a child can jump on their friend’s backpack when the floor is lava. At times they may also have to remind others that they are playing: if Superman hurts another child, that means the former is taking the make-believe too seriously. The stark contrast between ‘reality’ and ‘fantasy’ – the terms adults use to explain Western children’s behavior – bear little resemblance to the ‘being serious’ and ‘just kidding’ – the emic categories employed by my child interlocutors.

Once social evolutionism was (rightfully) cast off, children – then occupying a privileged position in anthropological debates – were unexpectedly thrown out with the bathwater, hardly being taken seriously alongside other interlocutors in ethnographies that are not strictly about children. As ‘Anthropological Theory’ becomes an ‘Anthropology of Adults and Adulthood’, children end up marginalized, taken seriously as interlocutors only within the subfield of Anthropology of Childhood, largely perceived as interlocutors who may as well be just kidding.

Header image: Poster produced by children between 6 and 7 years old from an elementary school in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The poster contains drawings and definitions of what memory is, in response to a classroom exercise. Image credit: Guilherme Fians.

Guilherme Fians is a social anthropologist working as a Leverhulme Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews (UK) and Co-Director of the Centre for Research and Documentation on World Language Problems (Netherlands/USA). In addition to his current research project on political engagements among Esperanto-speaking youth in the Cold War period, he has also researched meaning-making and children’s play. His projects have resulted in several publications, among which the Portuguese-language monograph Entre Crianças, Personagens e Monstros: Uma Etnografia de Brincadeiras Infantis (Among Children, Cartoon Characters, and Monsters: An Ethnography of Children’s Play).

August 2023

Young people leading positive social change in Fiji and Solomon Islands

When most people think about the Pacific, they imagine pristine beaches and warm nights. Those paying a bit more attention might consider the imminent risks of the climate crisis or the emerging danger of being geopolitically caught between China and the USA. What is unlikely to spring to mind is that the populations of Pacific island countries are predominantly made up of children and youth – and they’re only getting younger.

Despite the significance of young populations through the Pacific, little research has been conducted with, on or for Pacific youth. My book, Youth in Fiji and Solomon Islands: Livelihoods, leadership and civic engagement, (partially) fills this gap. Rather than being hyperfocused on a singular issue, such as the endemically high rates of youth unemployment, the book provides a political economic overview of the intersecting issues that lead to the ‘structural minimisation’ of Pacific youth, where ‘youth are to be seen but not heard’ (Tura Lewai, Fijian civil society activist).

Through conversations with youth activists and advocates, as well as ethnographic knowledge from experiences living and working in Pacific development spaces, the book explores the challenges and opportunities for young people in Fiji and Solomon Islands to achieve their individual and collective potential. Specific attention is paid to how a vicious circle has taken root in each country where youth needs and voice are considered unimportant, leading to education systems that aren’t fit for purpose, which exacerbates entrenched unemployment, with these problems continuing to go improperly addressed as youth needs and voices are considered unimportant.

Despite the hurdles they face, I document multiple instances of young people leading positive social change in their countries. Examples include the Pacific Climate Warriors leading global climate advocacy, Roshika Deo’s independent political campaign inserting social justice issues into the narrative for the 2014 Fiji election, and a Solomon Islands Facebook group that circumnavigated social barriers between youth and elders to hold their leaders to account. Just this year, the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change group was fundamental in having the UN General Assembly recommend an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice on the legal implications of the climate crisis.

Domestic realpolitik would suggest that the only reason for leaders to change the way they think about youth is because, ‘we hold the highest majority of the mandate’ (Jope Tarai, Fijian academic). But this book doesn’t deal in realpolitik, it deals in the real world of everyday young people in Fiji and Solomon Islands. And it shows that if they are given opportunities to contribute to their communities, countries and cultures, they can make positive change happen.

Aidan Craney is a Research Fellow at La Trobe University on the ARC Discovery Project, The future of the Pacific: Youth leadership and civic engagement. He has over a decade of experience in development and research roles in the Pacific islands region, with a focus on youth, political economy and locally led development.

July 2023

Who matters in child development? Peers and other caregiver roles in fostering children’s development in Rural Madagascar

If we think of an infant or a toddler – who else comes into mind? Is it perhaps the mother or father? Early childhood research and intervention usually focus on parents as presumably most influential figures in young children’s lives. This seemingly trivial fact has far-reaching consequences. In early intervention, for example, children’s opportunities for early learning or socio-emotional development are usually assessed through the mother-child interaction. But what if mothers in a particular community do not play or talk much with their infants and toddlers, while these children play and talk a lot with other children? Their cognitive development would be severely underestimated.

This scenario is true for a rural community of pastoralists in Madagascar: From early on children experience cognitively and affectively stimulating social interaction with other, similar-aged children. Mothers and other caregivers like preadolescent siblings or cousins are important too, however in different ways. They foster physical wellbeing, safety, and a calm state of infants and toddlers. Such a role division among children’s social partners appears to be common around the world according to the ethnographic record, especially when looking beyond middle-class, nuclear family settings. Therefore, the influential claim of early intervention, that the majority of young children in the global South do not have adequate opportunities for early learning and suffer from poor brain development, is more than doubtful.

To counter the parent-centric bias in much early childhood research and to foster a more comprehensive understanding of children’s social world across cultures, I propose the notion of complementary role division. I pitch this notion against the established hierarchical understanding, which ranks caregivers according their assumed significance for the child – from parents, to other caregivers, to peers. It builds on and specifies the concepts of multiple caregiving or distributed care. While these notions point to the fact that children may be raised by more individuals than just the parents, they still cling to parent’s primary roles of caregiving. Complementarity by contrast, incites to attend how all actors in children’s social world, whether caregivers or not, whether older or younger, complement each other by providing different social experiences. Finally, I argue that due to complementary role distribution, children may simultaneously acquire several context-dependent modalities of relationship, emotion, and self.

Read Scheidecker’s article here

Gabriel Scheidecker is Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, University of Zurich. He has conducted long-term ethnographic research about childrearing, and emotion socialization in Madagascar and about immigrant parenting and parenting support within Vietnamese migrant settings in Berlin. In his current roles as PI of the SNSF Starting Grant “Saving Brains?” he critically engages with the science and politics of early childhood interventions in the global South. His previous publication is: Scheidecker, G., Chaudhary, N., Keller, H., Mezzenzana, F., & Lancy, D. F. (2023). “Poor brain development” in the global South? Challenging the science of early childhood interventions. Ethos 51(1), 3-26

June 2023

Girls Who Kick Back: A new ethnography on street soccer, gender and Muslim youth in the Netherlands

Van Den Bogert, Kathrine. 2023. Street Football, Gender and Muslim Youth in the Netherlands: Girls Who Kick Back. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350205079.

Girls’ soccer is one of the fastest growing sports in the world. But do girls with diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds equally play soccer? And how is the growth of girls’ soccer reflected in urban public spaces where girls and boys compete in the access to those spaces?

With those questions in mind, I joined street soccer games and trainings in Dutch a multicultural and multi-religious neighbourhood, the Schilderswijk. Already the focus on girls in the masculine world of (street) soccer proved the relevance of this topic. Girls were thrilled that I was there to speak to them, and not to the boys. The interest of a researcher in their girls’ street soccer games, was the recognition that they counted as real street soccer players. The boys, on the other hand, were often a bit annoyed that I wasn’t there to speak to them in the first place, and sometimes even demanded to be interviewed too. However, during the course of the research I found out that the gender segregation often so prominent in sports, wasn’t that clear-cut in the street soccer competition that the girls organized the neighbourhood.

This book takes you to the performances of masculinity, femininity and heteronormativity in street soccer playgrounds through the eyes and plays of teenage girls and boys. Moreover, it shows how Moroccan-Dutch and Muslim girls navigate the gendered, racialized and secularized public sport spaces in their neighbourhood, such as soccer courts, urban playgrounds and public squares. This ethnography is a tribute to the street soccer girls who kick back, not at the ball in the game, but also at racism and sexism in sport and society. Goal!

Read Van Den Bogert’s book here

Kathrine van den Bogert is an assistant professor at the Utrecht University School of Governance and the research group Sport and Society. She has a PhD in social anthropology and MA and postdoc in gender studies. Her expertise is on the themes gender, youth, diversity, sport, multicultural urban neighbourhoods and ethnic and religious diasporas in the Netherlands and Europe. Her first book ‘Street Football, Gender and Muslim Youth in the Netherlands: Girls Who Kick Back’ is published with Bloomsbury Academic and is based on long-term ethnographic research in the Schilderswijk in The Hague (the Netherlands). Kathrine has also conducted ethnographic research on youth social movements in Birmingham (UK) and Cairo (Egypt).

April 2023

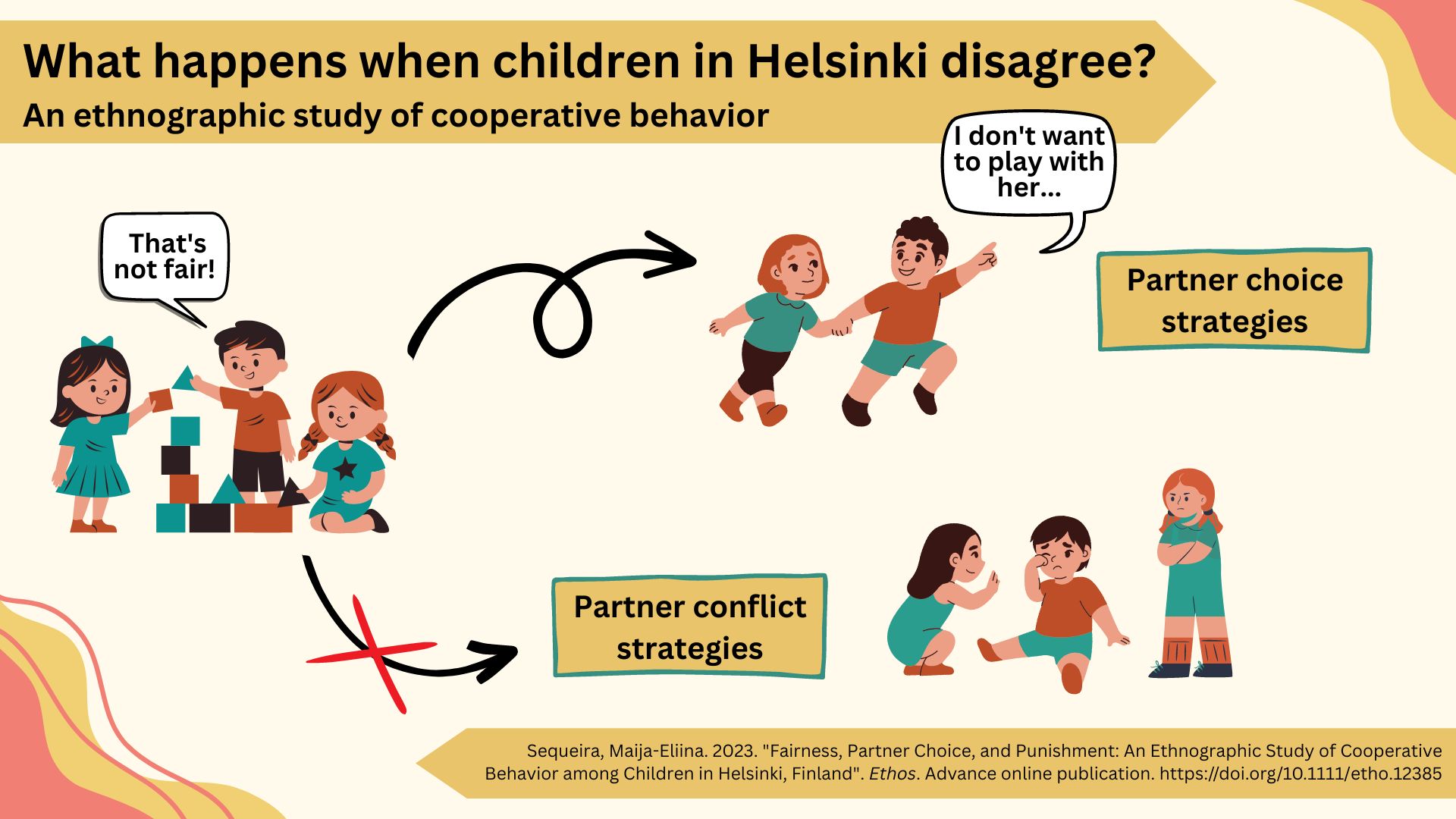

What happens when children disagree?

Click on visual abstract to view enlarged version

Sequeira, Maija-Eliina. 2023 “Fairness, Partner Choice, and Punishment: An Ethnographic Study of Cooperative Behavior among Children in Helsinki, Finland.” Ethos https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12385.

Maija Sequeira is a doctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. She is interested in how children learn and use social hierarchies in their everyday lives, and uses experimental and ethnographic methods in Finland and Colombia to explore this from both cross-cultural and developmental perspectives.

March 2023

How do young swimmers come to “sense” the water?

Heath, Sean. 2022. The Quality of Water: perception and senses of fluid movement. The Senses and Society, 17(3), p.263-276.

How does immersion in water shape young people’s senses, sense of self, and lifeworlds? From as early as six years old, competitive swimmers begin developing a ‘feel for the water’ through playful exploration of movement and tactile sensory experiences in water. Senses of touch must be cultivated and privileged from an early age to shape the sensorium of the swimmer. Over time, young people’s apprenticeship in swimming culminates in whole body changes in flexibility, mobility, and sense perception.

In learning to exploit the materiality of water and in becoming more immediately aware of its properties with the goal of swimming faster, going further with each stroke, and recovering more seamlessly, competitive youth swimmers enact an embodied sensory knowledge of water shaped through a sensorium that privileges touch sense modalities. In other words, swimmers can manipulate water and interact with it differently. Water additionally affords emotional pleasures in movement, over, under, on top, and with the liquid flow. Emotion and motion become entangled in swimming performances, past emotional experiences and present feelings of nerves, anxiety, or confidence can shift how the swimmer perceives the tangibility of water (whether their hand is ‘slipping’ or ‘anchoring’ in the water), and thus their own sense of self as a fast swimmer. Even an absence of immersion may heighten already honed senses, a few weeks out of the water bringing a subtle but forced awareness back into young people’s ‘feel for the water’ and their being-in-the-water.

Sean Heath is a Social Anthropologist specializing in the body, movement, well-being, the senses, and human-water interactions. He received his PhD in 2022 from the University of Brighton. He has conducted research with competitive swimmers in Canada and the UK which examined the sensory aspects of immersion in water and the sociality of club swimming and how these affect youths’ wellbeing. He has also examined the emplaced entanglements between the material, social, and emotional experiences of outdoor swimming in “natural” environments. In October 2023 he will commence a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions postdoctoral fellowship at KU Leuven to study human, more-than-human, and planetary wellbeing in the entangled relationships between arctic waters, the senses, and place.

Find out how to submit your work to the Spotlight on Scholarship

October 2022

When smartphones hijack rapport…

Jovicic, Suzana, 2022. The Affective Triad: Smartphone in the Ethnographic Encounter. Media and Communication, 10(3):225-235. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i3.5331

Image credit: Zoran Zonde Stojanovski on Unsplash

Imagine nervously fumbling with your hands as you awkwardly stand in front of an unknown interlocutor, sweating out small talk that will ideally catapult you into a blissful state of trust and rapport. Looking around, you find yourself in a youth centre on the outskirts of Vienna, Austria, facing an unimpressed teenager leaning on a sofa, surrounded by peers who are all very adept at avoiding eye contact. And now add the smartphone…. Now you can only assume you are looking at an unimpressed teenager because you now stare at top of his head while he looks at his smartphone and scrolls through the endless social events – so you assume. Now get on with the fieldwork and good luck.

It didn’t take long for a feeling of desperation to set in as I began my fieldwork in Vienna’s youth centres, hanging out in the municipally funded recreational spaces for children and young people between the ages of 5 and 21. As a digital anthropologist later dubbed “the internet woman”, I was fascinated by smartphones, which seemed like impenetrable black boxes that at the same time exuded an air of warmth and intimacy towards the owners while remaining cold towards the researcher. They seem to disrupt the potential for connection and place a cloak of invisibility over their owners, enveloping them in a bubble of privacy. Over time, however, smartphones morphed into highly ambiguous and shape-shifting objects, sometimes living up to their commercially popular image as connecting devices, opening doors to conversations, shared videos or transnational connections. But sometimes they also signalled temporary absence or deliberate withdrawal – both processes closely linked to the natural ebb and flow of (ethnographic) relationships. The young people described finely tuned, deliberate social choreographies around the smartphone, far from the zombification lamented in popular media. The fact that I did not initially see this dance does not mean that it does not exist.

As I argue in this article, ethnographic relationships may have always contained discomfort, but the appearance of alien objects in the middle shakes things up, albeit in unexpected ways. It can help us re-examine what rapport actually means, how we can explicitly negotiate privacy, which in this case is not just a diffuse concept, but strangely embodied in an externalised object. The ambiguity of such a slippery object itself becomes a constant reminder that privacy and relationship are dynamic processes – when smartphones are offered to the prying eyes of an ethnographer, or perhaps used demonstratively to avoid them. Such an avoidance needs to be given sufficient space, especially in our research with minors and vulnerable populations.

Suzana Jovicic is an Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) postdoctoral fellow and lecturer at the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Vienna; and co-PI of the “We-Design” interdisciplinary project that combines ethnographic research on the role of digital technologies in relation to the labour access among Viennese youth with participatory design and app development. Her interests lie in the areas of digital, design and psychological anthropology, youths, and participatory research. She is co-founder of the Digital Ethnography Initiative (DEI) at the University of Vienna and co-convenor of the European Network for Psychological Anthropology (ENPA).

August 2022

What were Jewish children’s roles in

surviving Europe’s Holocaust?

Rosen, David, 2022. Jewish Child Soldiers in the Bloodlands of Europe. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003193487

During World War II, thousands of Jewish children became members of armed partisan groups in Eastern Europe. This book describes and analyzes the role of children as activists, agents, and decision makers in a situation of extraordinary danger and stress. The children in this book were hunted like prey and ran for their lives; they survived the Holocaust by fleeing into the forest and swamps of Eastern Europe and joining anti-German partisan groups. Most of them were pre-teens and teenagers between ages 11 and 18, although some were younger. They were, by any definition, child soldiers, and that is the reason they lived to tell their tales.

The evidence and argument presented in this book run counter to the accepted wisdom that child soldiers are primarily victims of their recruiters. It asks what a child’s right of self-defense actually is, and how it is possible to assert this right when the principal institutions of society – including the schools, the judiciary, and the police – are specifically targeting children and there are no safe spaces remaining. There are numerous situations in which society is the enemy of the child, including not only the egregious example of Holocaust, but other instances of genocide, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Clearly time, place, and context are keys to our understanding of children’s involvement in war; Indeed, in some contexts children under arms must be seen as exercising an inherent right of self-defense that supersedes child protectionist concerns.

Purchase David’s book here: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781003193487/jewish-child-soldiers-bloodlands-europe-david-rosen

David M. Rosen is Professor of Anthropology and Law at Fairleigh Dickinson University, Madison, New Jersey. He received his Ph. D from the University of Illinois and his J.D. from Pace University School of Law. He has carried out research in Kenya, Sierra Leone, Israel and Palestine with special interest in children and armed conflict. His recent books include Jewish Child Soldiers in the Bloodlands of Europe (2022), Child Soldiers in the Western Imagination: From Patriots Victims (2015) and Armies of the Young: Child Soldiers in War and Terrorism (2005).

Hasemann Lara, José E. 2022. “Care in Ruination: Accessing Children’s Critiques of Health Through Playwriting.” Medical Anthropology 0 (0): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2022.2053966.

How do children think about the world? How do children take information about the world around them and make sense of it? What is unique about how children engage with the world and represent their worlds to others?

I started working with children in Honduras without first pausing to think about these questions. I assumed children’s perspectives were just another window into adults’ worlds. I was wrong.

Before sitting down to work on plays with two groups of children, I had several opportunities to observe how the children made sense of their worlds as subjects in-the-world. I watched some of the children reenact the migration route to the USA as a game. I talked with some of them about migration in their own families and their feelings and expectations. I gossiped excitedly with other children about witchcraft and evangelical Pentecostalism in their neighborhoods. I also listened to them discuss the spread of infectious diseases in their neighborhoods and public health care services. In the plays the children wrote, I watched the children grapple with themes like substance abuse and domestic violence, as well as solidarity. They traced and described complicated ideas borrowing from their own experiences and local TV shows.

The children were aware of inequality, class difference, urban precarity, and social welfare, and wove all of it into their stories. Through their plays, the children also challenged the world as it was/is by elaborating on alternate futures. The children reconfigured the social relations that bind a place like urban Honduras to present a more equitable potential social landscape. It was thrilling to get a glimpse of a shared world through their eyes.

Access José’s article here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01459740.2022.2053966

José Enrique Hasemann Lara holds a Ph.D. in anthropology (UCONN, 2021) and a M.A. in applied biocultural medical anthropology (USF, 2011) and M.P.H. in global communicable diseases (USF, 2011). His past research has focused on public health, inequality, racialization, and the unequal distribution of access to public goods in the urban landscapes of Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela, Honduras.

Find out how to submit your work to the Spotlight on Scholarship