by Lauren Silver

Associate Professor of Childhood Studies

Rutgers University-Camden

Six years ago, I remember beginning my new faculty role with excitement and trepidation. I was joining an interdisciplinary Department of Childhood Studies at Rutgers University-Camden. What unique attributes of a course in Youth Identities, for instance, could be communicated through a childhood studies lens? Needless to say, I haven’t discovered a formula; but I want to share a couple of principles—proximity and changing the narrative—that have guided my scholarship and approach to teaching childhood studies.

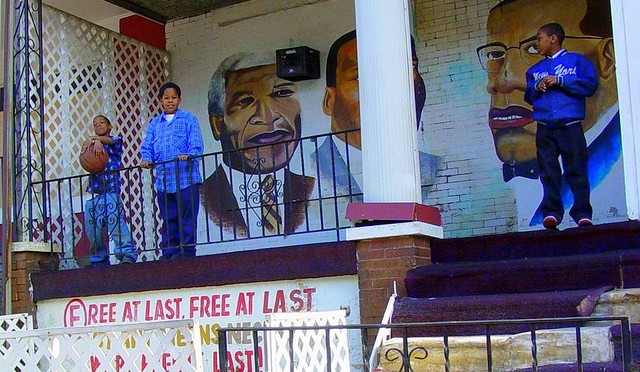

I borrow these principles from Bryan Stevenson, the Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative. He explained in his 2015 Rutgers Camden Convocation speech that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; it is justice. Bryan Stevenson believes that we can make the world more just but in order to do so, we must get close to those who are most oppressed in our society—to pay attention to suffering, poverty, exclusion, and injustice. Through proximity, there exists the potential to know others better and to tell stories that honor human dignity and complexity. Bells went off for me: yes, proximity has always guided my teaching and research! In order to get close to youth marginalized through race, poverty, gender, location, and sexuality—to understand their worlds in depth—I began a journey many years ago as a feminist ethnographer.

My book, System Kids: Adolescent Mothers and the Politics of Regulation (2015, UNC Press), is based on my experiences as a social worker and two years of ethnographic research with young mothers, navigating a large, urban child welfare system. “System kids” experience simultaneous and shifting statuses as  parents, teenagers, students, delinquents, dependents, and black girls. However, policymakers and scholars tend to consider these youth through unitary identities, either as students, delinquents, or adolescent mothers. Through one-dimensional viewpoints, we cannot recognize the challenges youth deal with while negotiating multiple systems and multiple roles at once. I shadowed young mothers across service settings and residences because I wanted to understand their trajectories and how the girls themselves perceived their identity performances. Closeness allowed me to recapture the coherence of youth narratives and to call attention to the harmful effects of disconnected systems.

parents, teenagers, students, delinquents, dependents, and black girls. However, policymakers and scholars tend to consider these youth through unitary identities, either as students, delinquents, or adolescent mothers. Through one-dimensional viewpoints, we cannot recognize the challenges youth deal with while negotiating multiple systems and multiple roles at once. I shadowed young mothers across service settings and residences because I wanted to understand their trajectories and how the girls themselves perceived their identity performances. Closeness allowed me to recapture the coherence of youth narratives and to call attention to the harmful effects of disconnected systems.

Elsewhere, I wrote about how I’ve used civic engagement in class to facilitate proximity between undergraduates and children in Camden’s public schools. Yet, even when civic engagement is not structured into my courses, classroom discourse can inspire students to make deeper connections with youth and communities outside of class. My students use course materials to explore the ways urban location and unjust relationships shape who gets to be the storyteller, as well as what can be told and what tends to remain silent. Centering children’s voices, a key tenet of childhood studies, means finding ways to consider a wider range of diverse storytellers. To encourage my students to engage, I teach ethnographic texts with youth-created poetry, short stories, video, photography, and spoken word. Also, my students do the same through offering creative multi-media group presentations inspired by course texts. During one group presentation, students complemented a clip from a youth’s spoken word performance about the burdens of hypermasculinity with a chapter from Victor Rios’ Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys.

I like to teach books in which ethnographers shadow youth across urban settings because these works resist the indignity of shortsighted and punitive stories about young people who are dealing with unfair circumstances. For instance, in System Kids, I shadowed one young mother, Nyisha, across multiple encounters with public housing authorities.

Soon after receiving a residence, I visited Nyisha in her new home. Nyisha shared how she had performed her identity as a “black girl” who was a rape victim so that the white male administrator would find her deserving of a public housing residence. She knew she couldn’t simply request assistance; she sought to influence outright this official’s regard for her personhood. In my prior role as her social worker, I had counseled her during the aftermath of the trauma. Yet, in the encounter with the official and in the storytelling to me about the encounter, she separated her emotions from her performance as a victim. Shadowing as a practice provides a window into multi-faceted identity work—shedding light on how power operates through a matrix of gender, race, class, and age divisions. In teaching these scenarios, I hope students will recognize Nyisha’s ingenuity and resourcefulness. I also want students to pay attention to the unjust system norms that compelled Nyisha to expose her trauma in order to receive a basic necessity, safe housing.

Victor Rios engages the practice of shadowing in his book Punished.  He shadowed Tyrell, Jose, and other youth of color across their everyday lives in Oakland, CA. He explored the boys’ stories and revealed his own narrative as a former gang member and incarcerated young person. Through these stories, my students learn about how young males are criminalized over time and space, not only through racial profiling from police in their impoverished neighborhoods, but also in schools, through their teachers’ harsh assumptions, and even through interactions with parents. These youth are constructed across sectors as violent. Students shared that they found this text meaningful when paired with the provocative spoken word poetry. They commiserated emotionally as well as intellectually with the burdens of hypermasculinity, racism, and institutional violence.

He shadowed Tyrell, Jose, and other youth of color across their everyday lives in Oakland, CA. He explored the boys’ stories and revealed his own narrative as a former gang member and incarcerated young person. Through these stories, my students learn about how young males are criminalized over time and space, not only through racial profiling from police in their impoverished neighborhoods, but also in schools, through their teachers’ harsh assumptions, and even through interactions with parents. These youth are constructed across sectors as violent. Students shared that they found this text meaningful when paired with the provocative spoken word poetry. They commiserated emotionally as well as intellectually with the burdens of hypermasculinity, racism, and institutional violence.

Similar to my approach in System Kids, where I show the taken-for-granted discourses concerning the so-called irresponsible or conniving teen mom, Rios shows the social construct of the presumed violent delinquent young male. I teach other works in which researchers shadow youth across urban settings including Nikki Jones’ book, Between Good and Ghetto: African American Girls and Inner-City Violence and Kathleen Nolan’s Police in the Hallways: Discipline in an Urban High School.

Erik Erikson’s sentiment in 1960 unfortunately still rings true:

“Juvenile delinquents are made, not born; and we adults make them.”

The ethnographies that I teach show how this making happens and how institutions, communities, as well as structural inequalities inform these identity constructions. My students shared how course materials enable them to experience vicariously the multifaceted journeys of ethnographers and youth across their cities. Ethnographic shadowing and multi-media storytelling inspire my students and me to challenge and resist “common sense” assumptions about naturally “bad” and “good” kids. Through both proximity and shifting narratives in university classrooms we can learn about multi-dimensional identities, and thus begin to reshape our world in more socially and racially just ways.